In a recent Economix blog, Bruce Bartlett explores the role “financialization” has played in American (and global) economic stagnation:

“Economists are still searching for answers to the slow growth of the United States economy. Some are now focusing on the issue of “financialization,” the growth of the financial sector as a share of gross domestic product.”

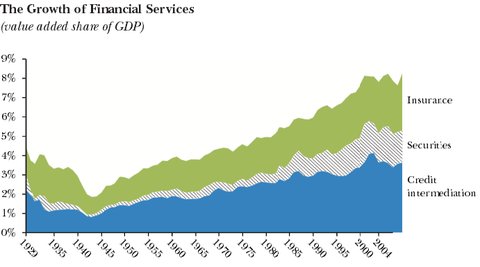

“According to a new article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives by the Harvard Business School professors Robin Greenwood and David Scharfstein, financial services rose as a share of G.D.P. to 8.3 percent in 2006 from 2.8 percent in 1950 and 4.9 percent in 1980. The following table is taken from their article.”

They cite research by Thomas Philippon of New York University and Ariell Reshef of the University of Virginia that compensation in the financial services industry was comparable to that in other industries until 1980. But since then, it has increased sharply and those working in financial services now make 70 percent more on average.”

“While all economists agree that the financial sector contributes significantly to economic growth, some now question whether that is still the case. According to Stephen G. Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi of the Bank for International Settlements, the impact of finance on economic growth is very positive in the early stages of development. But beyond a certain point it becomes negative, because the financial sector competes with other sectors for scarce resources.”

“Ozgur Orhangazi of Roosevelt University has found that investment in the real sector of the economy falls when financialization rises. Moreover, rising fees paid by nonfinancial corporations to financial markets have reduced internal funds available for investment, shortened their planning horizon and increased uncertainty.”

“Adair Turner, formerly Britain’s top financial regulator, has said, “There is no clear evidence that the growth in the scale and complexity of the financial system in the rich developed world over the last 20 to 30 years has driven increased growth or stability.”

He suggests, rather, that the financial sector’s gains have been more in the form of economic rents — basically something for nothing — than the return to greater economic value.

Another way that the financial sector leeches growth from other sectors is by attracting a rising share of the nation’s “best and brightest” workers, depriving other sectors like manufacturing of their skills.”

“The rising share of income going to financial assets also contributes to labor’s falling share. As illustrated in the following chart from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, that share has fallen 12 percentage points since its recent peak in early 2001 and even more from its historical level from the 1950s through the 1970s.

Labor Share of Nonfarm Business Sector

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of LaborThe falling labor share results from various factors, including globalization, technology and institutional factors like declining unionization. But according to a new report from the International Labor Organization, a United Nations agency, financialization is by far the largest contributor in developed economies (see Page 52).

The report estimates that 46 percent of labor’s falling share resulted from financialization, 19 percent from globalization, 10 percent from technological change and 25 percent from institutional factors.

This phenomenon is a major cause of rising income inequality, which itself is an important reason for inadequate growth. As the entrepreneur Nick Hanauer pointed out at a Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee hearing on June 6, the income of the middle class is critical to economic growth because of its buying power. Mr. Hanauer believes consumption is really what drives growth; business people like him invest and create jobs to take advantage of middle-class demands for goods and services, which must be supported by good-paying jobs and rising incomes.”

“According to research by the economists Jon Bakija, Adam Cole and Bradley T. Heim, financialization is a principal driver of the rising share of income going to the ultrawealthy – the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution.”

“Among those pointing their fingers at financialization is David Stockman, former director of the Office of Management and Budget, who followed his government service with a long career in finance at Salomon Brothers and elsewhere. Writing in The New York Times, he recently said financialization was “corrosive” and had turned the economy into “a giant casino” where banks skim an oversize share of profits.

It’s not yet clear what public policies are appropriate to deal with the phenomenon of financialization. The important thing at this point is to be aware of it, which does not yet appear to be the case in Washington.”

—

A complementary practice that has accompanied “financialization” is the practice of “commoditization“:

“Commoditization” has led to food price volatility and food insecurity in the developing world. It also perpetuated the housing bubble–while it is true that mortgages were always financial products, the way the mortgage backed securities grouped mortgages together turned a practice that was once a means of saving into an opportunity for people to use the equity in their homes like credit cards. When the housing bubble burst, many people found their mortgages “under water”. While there is certainly an element of personal responsibility, the scope of the housing crisis was certainly deepened due to “financialization” and “commoditization”.

Financialization attracts the best and brightest away from other non-financial fields. When all these talented people are working in a saturated market (such as more traditional investments), a natural effect will be the creation of “innovative” financial products–“commoditization”. While commoditization creates short run value by making products more liquid, in the long run it leads to price volatility and bubbles.

Financialization has led to greater income inequality (as the vast majority of capital gains go to the ultra-wealthy), and diverts resources and man-power away from non-financial industries (the “real economy) due to higher fees paid to financial services (these resources could go to, say, MORE HIRING). It has also perpetuated destabilizing, high-speed, arbitrage-seeking investment.

It is interesting that Mr. Bartlett says that it is unclear what public policies should be used to correct for this misalignment of resources. The answers are there (and Bruce himself has mentioned some in previous posts), the problem is implementation, as the proper policy responses require transparency and international cooperation and coordination (due to the global nature of capital in the digital age in order to prevent “capital flight”). Therefore, these commitments are rife with incentives to cheat (“prisoner’s dilemma”) which makes it much harder to come to binding agreements.

One appropriate response is a financial transaction tax (FTT). Such a tax would deter short-run destabilizing trades that have accompanied “financialization” and “commoditization” and direct investments into more long-run wealth creating endeavors (think venture capitalism as opposed to high-speed trading). This would also temper the price volatility effect of “commoditization”.

Another appropriate response would be to have a global standard tax rate for short-run capital gains. By setting such a rate higher than regular income taxation, resources would be diverted away the financial sector and back into the real sector (are you seeing a theme here?). Financial bubbles would be less prevalent, as people would be more likely to hold their income in safer assets / reinvest it in non-financial assets. Due to the relative ease of making short-term capital gains, and differences in national income tax rates, a global short-term capital gains tax rate of 50% seems like a good baseline to start from. Long-term capital gains should be taxed like ordinary income, not at lower preferential rates.

—

“Financialization” and “commoditization” have had adverse effects on our real economy. The brightest people and an increasing share of national output have been diverted towards (generally) unproductive activities In the short run this leads to economic growth. But this growth in unsustainable; in the long run crises occur when these bubbles burst, which have adverse effects that reach far beyond the financial sector (due in part to “commoditization”).

Because public policies have allowed financial institutions to grow so powerful, the were able to become “too big to fail“, necessitating tax-payer backed bailouts.

It is a good sign that economists are scrutinizing these practices. If it can be proved that not only do these practices lead to crises, but also have adverse effects on growth, employment, consumption and equality during “good” times, then it will be much harder for politicians around the world to resist the call for greater financial industry accountability via higher taxation (despite the threats from vested interests; if global standards are established, the 0.1% are welcome to setup the Mars Stock Exchange is they so desire).

June 15, 2013 at 1:43 pm

Reblogged this on aschil2121muhammet and commented:

yess

LikeLike

June 15, 2013 at 1:43 pm

evettt

LikeLike

Pingback: Conflict Watch: Austerity v. Human Rights | Normative Narratives

June 15, 2013 at 6:41 pm

Interesting. Why do you think FTT would impact over commodization instead of HFT. relative to the size of the investments, the proposed tax is small. why do you feel that such a small disincentive would lead to meaningful change in the behavior of the economy’s actors?

LikeLike

June 16, 2013 at 10:30 pm

I think that a FTT would discourage both commoditization and HFT. I agree with you that it will probably be quite some time until a FTT has a meaningful effect, as it would likely have to be implemented at a very low level initially in order to come to any sort of agreement on the policy.

I also think a higher capital gains tax would have the same effect on both practices. Make the financial sector in some way less appealing, and over time resources will realign to more sustainable sectors. Considering the unquestionable negative externalities that financial markets have had on global welfare in recent years, a FTT and greater taxation on capital gains are a way of holding the financial sector accountable for its role in The Great Recession.

I am reading the study and taking away this message; not only does “too big to fail” leave the economy more vulnerable to a large crisis, even when times are “good” gains are not made in a way that promotes sustainable or equitable growth.

I may be reading too far into the study, but if your not reading for future policy implications, then you restrict the value of the findings.

LikeLike